California Pest Rating for

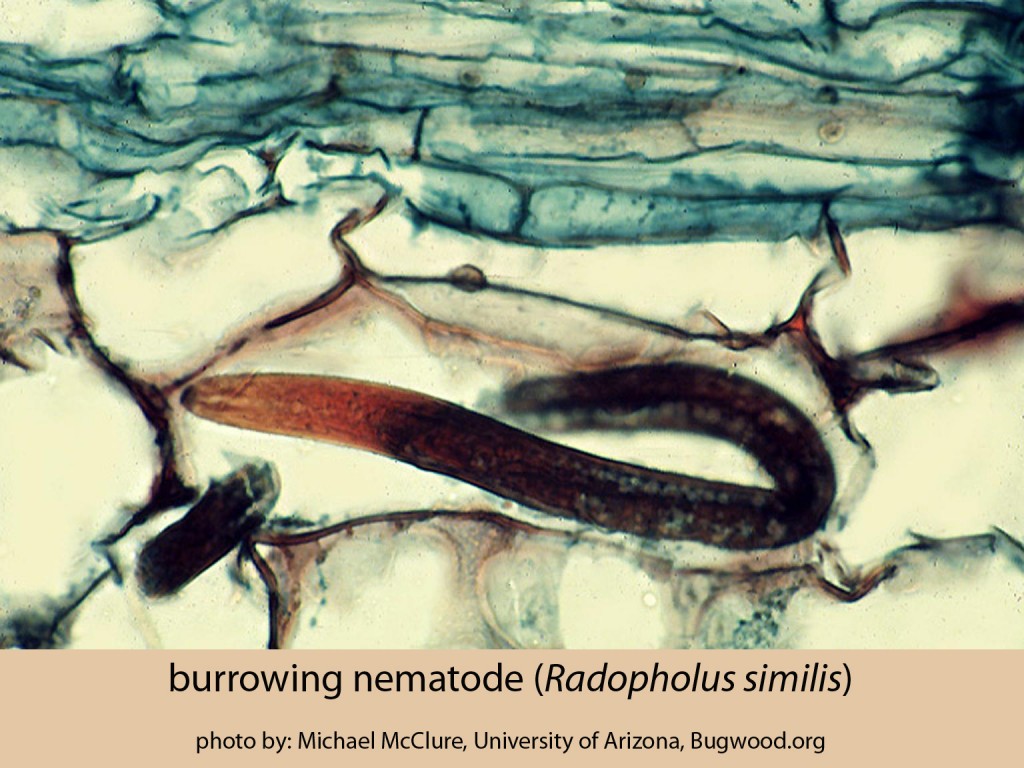

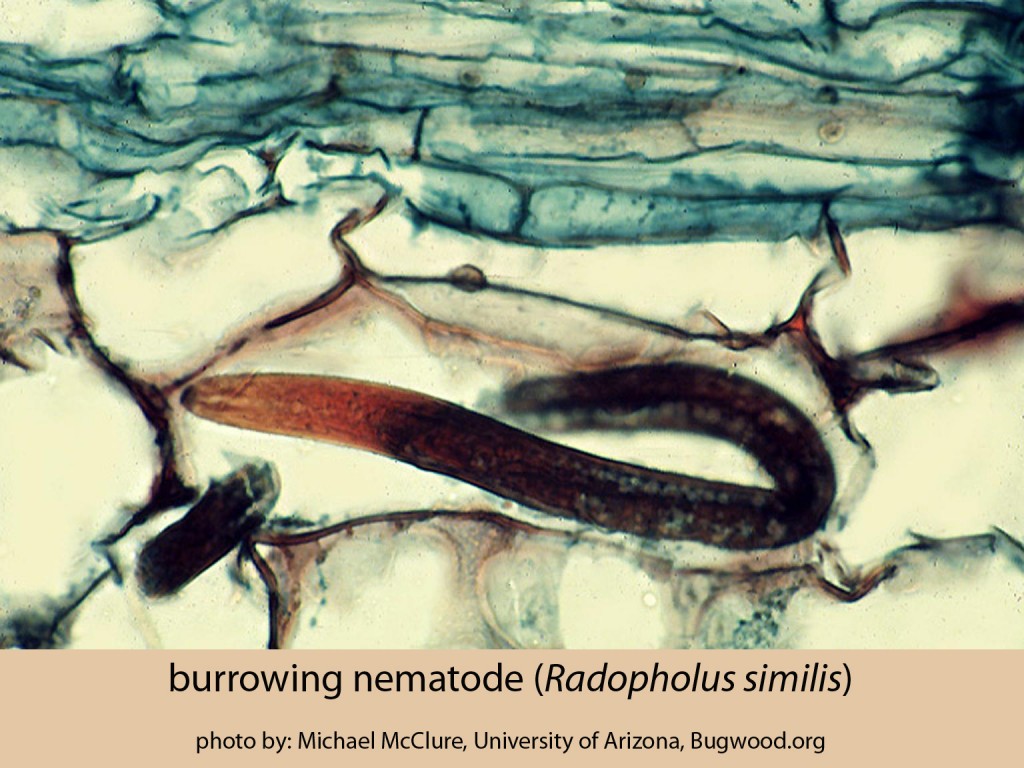

Radopholus similis (Cobb, 1893) Thorne, 1949

(Burrowing Nematode)

Pest Rating: A

PEST RATING PROFILE

Initiating Event:

None. The current status and rating of Radopholus similis is re-evaluated.

History & Status:

Background: The burrowing nematode, Radopholus similis, is one of the most economically important plant parasitic nematode in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. It is widespread in most banana-growing regions where it causes blackhead toppling disease or decline of banana. It is also known to cause declines of avocado, tea, coconut, citrus, and yellows (slow-wilt) disease of black pepper, and attacks several fruit, ornamentals, forest trees, sugarcane, coffee, weeds, vegetables, grasses, and weeds.

Radopholus similis has undergone several name changes over the past several years. In 1893, Cobb first described the nematode as Tylenchus similis associated with a serious disease of bananas in Fiji. From 1898 to 1915 the nematode was discovered in sugarcane in Hawaii, banana in Jamaica, and coffee in Java but described under different names which were later regarded as synonyms of T. similis. In 1949, Thorne established the genus Radopholus for the species originally belonging to Tylenchus, and T. similis became R. similis. Radopholus similis was known to have two biological races, a banana and citrus race. In 1984, the citrus race was elevated to species status and became known as R. citrophilus, separate from R. similis (Huettel, 1984). However, through molecular and morphological analyses, R. citrophilus was determined to be similar to R. similis and is now accepted as synonymous to the latter species (CABI, 2016; Kaplan & Opperman, 1997; Valette et al., 1998). For regulatory purposes, the CDFA has always regarded R. similis (sensu lato) to include both banana and citrus races (Chitambar, 1997).

Radopholus similis is a migratory endoparasite of plant roots. The nematode develops from egg through four larval stages to adult male and female which reproduce sexually and parthenogenetically. Radopholus similis completes its life cycle in 25 days at 25-28°C in coconut, 20-25 days at 24-32°C in banana, and 18-20 days at 24-27°C in citrus. The nematode species is able to complete its entire life cycle within the root cortex, however in adverse conditions, motile, vermiform larvae and adults may emerge from the roots and invade rhizosphere soils (EPPO, not dated; Tarjan & O’Bannon, 1984). The number of nematodes present in soil and roots varies with soil temperature, texture, moisture, and season. On citrus, R. similis is found at soil depths of 60-150 cm (DuCharme, 1967), and is more pathogenic to citrus in sandy soils than loam or sandy loam soils (O’Bannon & Tomerlin, 1971).

Hosts: Radopholus similis has a very wide host range of more than 350 known hosts although the pathogenicity of the nematode is not known for all hosts (Ferris et al., 2003). Main hosts include, Musa sp. (banana), M. textilis (Manila hemp), Musa x paradisiaca (plantain), Citrus spp. (citrus), Cocos nucifera (coconut), Zingiber officinale (ginger), palm, Persea americana (avocado), Coffea arabica (arabica coffee), C. canephora (robusta coffee), Piper nigrum (black pepper), Lycopersicum esculentum (tomato), Daucas carota (carrot),vegetables, trees, ornamentals, grasses, and weeds (CABI, 2016; Ford et al., 1960; Ferris, et al., 2003). In California, agricultural crops of economic importance include citrus, strawberry, carrots, and ornamentals.

Symptoms: Above ground symptoms are non-specific and include yellowing, stunting, reduction in number and size of leaves and fruit, delay in flowering, and overall sparse foliage of orchard trees. Infected trees wilt more readily than healthy trees under adverse environmental conditions (Griffith & Koshy, 1990; Tarjan & O’Bannon, 1984). Banana plants become uprooted and topple over, especially those burdened with fruit. Below ground symptoms include, brown to black lesions formed at the site of nematode penetration in citrus roots. These lesions coalesce to form cankers. A greater percentage of citrus feeder roots are destroyed below 75 cm than at 25-75 cm. In banana roots, dark red lesions appear on the outer root portion, penetrating throughout the cortex but not into the stele. Lesions may coalesce and girdle the root forming black, necrotic lesions which may extend into the corm (Gowen & Quénéhervé, 1990). Tender roots of coconut seedlings become spongy in texture and small, elongate orange lesions are formed in tender white roots. Lesions enlarge as rot sets in. Cracks in lesions may appears as lesions harden. Secondary and tertiary roots rot and slough off quickly on infestation (Griffith & Koshy, 1990).

Damage Potential: In Florida orchards, yield losses of 40-70% for oranges and 50-80% for grapefruit have been reported (DuCharme, 1968). Reduction in fruit production varies with age of the tree, citrus variety, farming practices and duration of the nematode infestation (CABI, 2016). Avocado trees show spreading decline symptoms similar to citrus. Several indoor decorative plants can be severely affected (Ferris, 2003). Nurseries may suffer significant losses in production.

Transmission: Infested nursery stock, propagative planting materials, bare root stock, corms, rhizomes, suckers, seedlings, rooted and non-rooted cuttings, soil, infested-soil contaminated cultivation tools and containers, irrigation water.

Brief update of detections in California: The CDFA has been protecting California against the burrowing nematode since the early 1950s when the nematode pathogen was first found to cause spreading decline of citrus in Florida. In the years that followed, statewide surveys revealed several ornamental nurseries to be infested with Radopholus similis and consequently, the nematode species was eradicated. In 1956, The Burrowing Nematode Exterior Quarantine (Sec. 3271) was established by CDFA to restrict the entrance of the pathogen from infested regions. In 1956, surveys of citrus and avocado orchards and ornamental nurseries, were conducted through the cooperative efforts of federal, state, and county agricultural commissioners. These surveys resulted in no detection of R. similis in CA. In 1963, the burrowing nematode was detected in Anthurium spp. in a nursery in San Mateo County. The plants were destroyed and the nematode was eradicated. From 1963-64, additional statewide surveys were conducted for Anthurium spp., citrus, and avocado in orchards, nurseries, and residential properties adjacent to nurseries. No R. similis was detected. In 1964, CDFA created the ‘Burrowing Nematode Detection Program in California Nurseries’ which terminated in 1994. Surveys continued in 1971, 2005-2009, and 2011 all which resulted in no detection of R. similis. Intercepted plant shipments imported to California under the Burrowing Nematode Exterior Quarantine continue to be examined for the burrowing nematode. A noteworthy early detection of an established R. similis population occurred in 1996 in a residential property in Huntington Beach. Consequently, the nematode was eradicated from the infested region (Chitambar, 2007). Since then, there have been no further detections of R. similis established in California and the pathogen is not known to be present in California.

Worldwide Distribution: The burrowing nematode is found worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions and occurs wherever bananas are grown. Worldwide distribution includes Asia: Brunei Darussalam, India, Indonesia, Japan, Lebanon, Malaysia, Oman, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Yemen; Africa: Benin, Burkino Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Congo Democratic Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, East Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Nigeria, Réunion, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe; North America: Canada, Mexico, USA; Central America and Caribbean: Barbados, Belize, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, French West Indies, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, Panama, Puerto Rico, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, United States Virgin Islands, Windward Islands; South America: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, Venezuela; Europe: Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Slovenia; Oceania: American Samoa, Australia, Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Micronesia, New Caledonia, Niue, Norfolk, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga (CABI, 2016; EPPO, 2016).

Official Control: Radopholus similis is a quarantine, A-rated nematode pest under CDFA Sec. 3271. Burrowing and Reniform Nematode State Exterior Quarantine. Areas under quarantine include, the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, and the commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

Radopholus similis is listed in the ‘Harmful Organism Lists’ for 32 countries including, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Chile, China, European Union, French Polynesia, Georgia, Guatemala, Holy See (Vatican City State), Israel, Japan, Jordan, Madagascar, Mexico, Monaco, Morocco, Namibia, Nepal, Norway, Panama, Paraguay, San Marion, Serbia, South Africa, Taiwan, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay, and Vietnam. Radopholus citrophilis (synonym of R. similis) is listed in the ‘Harmful Organism Lists’ for Antigua and Barbuda, Namibia, and South Africa; R. similis citrophilus (synonym of R. similis) is listed for Argentina, Brazil, European Union, French Polynesia, Grenada, Guatemala, Holy See (Vatican City State), Israel, Japan, Jordan, Monaco, Morocco, New Caledonia, San Marino, Serbia, Tunisia, Turkey, and Uruguay; Radopholus spp. is listed for Australia, French Polynesia, and Nauru (USDA PCIT, 2016).

California Distribution: Radopholus similis is not established in California.

California Interceptions: Since 1982 to September 2016, CDFA has made 182 detections of Radopholus similis and 13 detections of Radopholus sp. in incoming quarantine shipments of nursery and household plants at nurseries and border stations in California, of which only 16 detections of R. similis and 0 detections of Radopholus sp. were made during 2000-2016 (CDFA Pest and Damage Records Database).

The risk burrowing nematode would pose to California is evaluated below.

Consequences of Introduction:

1) Climate/Host Interaction: Evaluate if the pest would have suitable hosts and climate to establish in California. Score:

-Low (1) not likely to establish in California; or likely to establish in very limited areas

-Medium (2) may be able to establish in a larger but limited part of California

– High (3) likely to establish a widespread distribution in California.

Risk is High (3). California provides favorable climate and hosts for the establishment, increase, and widespread distribution of the burrowing nematode. The nematode prefers coarse, sandy soils which are present in the Coachella Valley, the Bard Valley near Blythe, the Edison-Arvin citrus district of Kern County, and in streaks throughout the state. Citrus and date palm, good hosts of the nematode, in the Coachella Valley are planted in soils subject to temperatures favorable to the development of the nematode. Host crops along the coastal areas, when planted in sandy soil, experience soil temperatures that can favor the development of the nematode if even for a few months.

2) Known Pest Host Range: Evaluate the host range of the pest:

-Low (1) has a very limited host range

-Medium (2) has a moderate host range

– High (3) has a wide host range.

Risk is High (3). Radopholus similis has a wide host range of over 350 host plants including citrus, strawberry, carrots, date palm, and ornamentals which are major hosts cultivated in California.

3) Pest Dispersal Potential: Evaluate the dispersal potential of the pest:

-Low (1) does not have high reproductive or dispersal potential

-Medium (2) has either high reproductive or dispersal potential

– High (3) has both high reproduction and dispersal potential.

Risk is High (3). Radopholus similis has both high reproduction and dispersal potential. It is spread over long and short distances by infected plant roots, soil, planting stock, rooted and non-rooted cuttings, weeds, soil, nematode-contaminated cultivation tools, and containers, planting beds, irrigation and run-off water.

4) Economic Impact: Evaluate the economic impact of the pest to California using these criteria:

A. The pest could lower crop yield

B. The pest could lower crop value (includes increasing crop production costs)

C. The pest could trigger the loss of markets (includes quarantines by other states or countries)

D. The pest could negatively change normal production cultural practices

E. The pest can vector, or is vectored, by another pestiferous organism.

F. The organism is injurious or poisonous to agriculturally important animals.

G. The organism can interfere with the delivery or supply of water for agricultural uses

-Low (1) causes 0 or 1 of these impacts

-Medium (2) causes 2 of these impacts

– High (3) causes 3 or more of these impacts.

Risk is High (3). The establishment of Radopholus similis in California could result in lowered crop yield and value, increased crop production costs, loss of markets, imposition of domestic and international quarantines against California export plant commodities, and alteration of normal cultural practices, including delivery of irrigation water, to inhibit spread of the pathogen to non-infested sites. Citrus, strawberry, carrots, date palms, and ornamentals are some of the main industries that would be affected. Additionally, several other crops of lesser production in California are also at risk.

5) Environmental Impact: Evaluate the environmental impact of the pest on California using these criteria:

A. The pest could have a significant environmental impact such as lowering biodiversity, disrupting natural communities, or changing ecosystem processes.

B. The pest could directly affect threatened or endangered species.

C. The pest could impact threatened or endangered species by disrupting critical habitats.

D. The pest could trigger additional official or private treatment programs.

E. Significantly impacting cultural practices, home/urban gardening or ornamental plantings.

Score the pest for Environmental Impact:

– Low (1) causes none of the above to occur

– Medium (2) causes one of the above to occur

– High (3) causes two or more of the above to occur.

Risk is High (3). The establishment of Radopholus similis in California could adversely impact the environment by destroying natural communities, critical habitats, significantly affect residential gardening and cultural practices thereby requiring additional official or private treatment programs. Given its wide host range several, agricultural and environmental communities are at definite risk of being impacted. These can include habitats of minor and major animal communities.

Consequences of Introduction to California for Common Name: Score

Add up the total score and include it here. (Score)

Low = 5-8 points

Medium = 9-12 points

High = 13-15 points

Total points obtained on evaluation of consequences of introduction to California = 15 (High).

6) Post Entry Distribution and Survey Information: Evaluate the known distribution in California. Only official records identified by a taxonomic expert and supported by voucher specimens deposited in natural history collections should be considered. Pest incursions that have been eradicated, are under eradication, or have been delimited with no further detections should not be included. (Score)

–Not established (0) Pest never detected in California, or known only from incursions.

-Low (-1) Pest has a localized distribution in California, or is established in one suitable climate/host area (region).

-Medium (-2) Pest is widespread in California but not fully established in the endangered area, or pest established in two contiguous suitable climate/host areas.

-High (-3) Pest has fully established in the endangered area, or pest is reported in more than two contiguous or non-contiguous suitable climate/host areas

Evaluation: Radopholus similis is not established in California (0). In 1996, the nematode species was discovered in a residential area in Huntington Beach, California, however, due to the early detection and isolated nature of the incident, the infestation was successfully eradicated by the CDFA. Similarly, eradicative actions taken subsequent to the detection of the nematode species in imported nursery and household plant shipments, vigilant screening of plant materials grown in California soils and inspected for plant parasitic nematodes through CDFA’s phytosanitary certification programs, USDA CAPS sponsored statewide surveys conducted by CDFA from 2005-2009 for 22 target nematode species including R. similis, and all published studies to date on plant parasitic nematodes in California have never resulted in the detection of R. similis.

Final Score:

Final Score: Score of Consequences of Introduction – Score of Post Entry Distribution and Survey Information = 15 (High).

Uncertainty:

The damage potential and crop loss information on several hosts of this nematode species are yet to be determined. Nevertheless, based on the nematode’s biology, diverse host range, and favorable climatic conditions that (historically have) allowed the pest to establish within California (and then be eradicated), more information gained on crop damage and losses can only further confirm the burrowing nematode as a pest of major economic importance within several regions of California.

Conclusion and Rating Justification:

Based on the evidence presented above, reniform nematode is definitely a pest of high risk to agricultural and environmental communities of California. The current given “A” pest rating of Radopholus similis is duly justified and is herein, proposed to remain unchanged.

References:

CABI. 2016. Radopholus similis (burrowing nematode) datasheet (full). http://www.cabi.org/cpc/datasheet/46685

Chitambar, J. J. 1997. A brief review of the burrowing nematode, Radopholus similis. California Plant Pest & Damage Report, California Department of Food and Agriculture, 16: 66-70.

Chitambar, J. J. 2007. Status of ten quarantine “A” nematode pests in California. California Plant Pest & Damage Report, California Department of Food and Agriculture, 24: 62-75.

DuCharme, E. P. 1967. Annual population periodicity of Radopholus similis in Florida citrus groves. Plant Disease Reporter 51: 1013-1034.

DuCharme, E. P. 1968. Burrowing nematode decline of citrus. A review. In: Smart GC, Perry VG, eds. Tropical Nematology. Gainesville, USA: University of Florida Press, 20-37.

EPPO. 2016. Radopholus similis (RADOSI). PQR database. Paris, France: European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization.

EPPO. Not dated. Data sheets on quarantine pests Radopholus citrophilus and Radopholus similis. Prepared by CABI and EPPO for the EU under Contract 90/399003. https://www.eppo.int/QUARANTINE/data_sheets/nematodes/RADOSP_ds.pdf

Ferris, H., K. M. Jetter, I. A. Zasada, J. J. Chitambar, R. C. Venette, K. M. Klonsky, and J. Ole Becker. 2003. Risk Assessment of plant parasitic nematodes. In Exotic Pests and Diseases Biology and Economics for Biosecurity, D. A. Summer Editor. Iowa State Press. 265 p.

Ford, H. W., W. A. Feder, and P. C. Hutchins. 1960. Citrus varieties, hybrids, species and relatives evaluated for resistance to the burrowing nematode Radopholus similis. Plant Disease Reporter 44:405.

Gowen, S., and P. Quénéhervé. 1990. Nematode parasites of bananas, plantains and abaca. In: Luc, M., R. A. Sikora, J. Bridge, eds. Plant Parasitic Nematodes in Subtropical and Tropical Agriculture. Wallingford, UK: CAB International, 431-460.

Griffith, R., P. K. Koshy. 1990. Nematode parasites of coconut and other palms. In: Luc, M., R. A. Sikora, J. Bridge, eds. Plant Parasitic Nematodes in Subtropical and Tropical Agriculture. Wallingford, UK: CAB International, 363-386.

Huettel, R. N., D. W. Dickson, and D. T. Kaplan. 1984. Radopholus citrophilus n. sp., a sibling species of Radopholus similis. Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington 51: 32-35.

Kaplan, D. T., and C. H. Opperman. 1997. Genome similarity implies that citrus-parasitic burrowing nematodes do not represent a unique species. Journal of Nematology, 29: 430-440.

O’Bannon, J. H., and A. T. Tomerlin. 1970. Response of citrus seedlings to Radopholus similis in two soils. Journal of Nematology 3: 255-260.

USDA PCIT. 2016. USDA Phytosanitary Certificate Issuance & Tracking System. September 27, 2016. https://pcit.aphis.usda.gov/PExD/faces/ReportHarmOrgs.jsp.

Valette, C., D. Mouonport, M. Nicole, J. L. Sarah, and P. Baujard. 1998. Scanning electron microscope study of two African populations of Radopholus similis (Nematoda: Pratylenchidae) and proposal of R. citrophilus as a junior synonym of R. similis. Fundamental and Applied Nematology 21: 139-146.

Responsible Party:

John J. Chitambar, Primary Plant Pathologist/Nematologist, California Department of Food and Agriculture, 3294 Meadowview Road, Sacramento, CA 95832. Phone: (916) 262-1110, plant.health[@]cdfa.ca.gov.

Comment Period: CLOSED

Oct 5 – Nov 19, 2016

Comment Format:

♦ Comments should refer to the appropriate California Pest Rating Proposal Form subsection(s) being commented on, as shown below.

Example Comment:

Consequences of Introduction: 1. Climate/Host Interaction: [Your comment that relates to “Climate/Host Interaction” here.]

♦ Posted comments will not be able to be viewed immediately.

♦ Comments may not be posted if they:

Contain inappropriate language which is not germane to the pest rating proposal;

Contains defamatory, false, inaccurate, abusive, obscene, pornographic, sexually oriented, threatening, racially offensive, discriminatory or illegal material;

Violates agency regulations prohibiting sexual harassment or other forms of discrimination;

Violates agency regulations prohibiting workplace violence, including threats.

♦ Comments may be edited prior to posting to ensure they are entirely germane.

♦ Posted comments shall be those which have been approved in content and posted to the website to be viewed, not just submitted.

Pest Rating: A

Posted by ls