California Pest Rating for

Ditylenchus destructor Thorne, 1945

Pest Rating: A

PEST RATING PROFILE

Initiating Event:

On June 1, 2016, the USDA added Ditylenchus destructor to the ‘List of Pests No Longer Regulated at U.S. Ports of Entry’. Consequently, the risk of introduction and establishment of Ditylenchus destructor in California is evaluated and the current rating is reviewed.

History & Status:

Background: Ditylenchus destructor was described by Thorne as a valid species in 1945. However, prior to 1945, it was regarded as a strain or race of Ditylenchus dipsaci – the stem and bulb nematode. Therefore, much of the earlier literature provides confusing information on the two species especially in relation to potato. Both species are distinctly differentiated from each other morphologically and molecularly.

Ditylenchus destructor, commonly known as the potato rot nematode after its principal host, is a plant parasitic nematode that causes significant loss in crop production mainly of potato, iris, and several other crops. Ditylenchus destructor is a migratory endoparasite of roots and underground subterranean modified plant parts such as tubers, stolons, bulbs, and rhizomes, and rarely invades above-ground parts, mainly the stem base (EPPO, 2008). The nematode species is also capable of feeding and reproducing on several fungal species and can destroy the hyphae of cultivated mushroom (Agaricus hortensis). Nematodes enter potato tubers through lenticels, rapidly multiply and invade the entire tuber within which they continue to develop and increase in numbers. External lesions subsequently serve as avenues for secondary infections by other pathogens. The nematode species secretes enzymes that digest starch and proteins and cause cell disintegration or rot of the infected plant parts. Generally significant damage to potatoes can occur at cool temperatures (15-20°C) and high relative humidity (90%) (CABI, 2016).

Ditylenchus destructor has been reported from several countries including limited regions within the USA (see ‘Worldwide Distribution”).

Status of detections in California: For long, the potato rot nematode has been cited in scientific publications as being present in California. An up-to-date, brief review of detections of the nematode pathogen in California is presented here. In California, the first recorded instance of potato tuber rot caused by D. destructor, was in 1968 in an experimental planting of potatoes in infested soil at Muir Beach, Marin County (Ayoub, 1970). During the late 1950s to mid-1970s, CDFA recorded few detections of D. destructor only in iris bulbs from nurseries in Humboldt, Contra Costa, San Diego, and Santa Cruz Counties, few detections, also in iris bulbs, from residential/dooryard environments in San Diego, San Francisco, and San Luis Obispo Counties, and few detections from commercial environments in Marin and Santa Cruz Counties. The most recent detection was in 1995 from round-headed garlic (Allium sphaerocephalum) bulbs in a nursery in Santa Cruz County (CDFA Nematology Laboratory Pest and Damage Records). There have been no other reports of potato rot nematode detections in California’s agricultural and natural environments. Viglierchio’s (1978) report of D. destructor infesting Ponderosa pine in California has sometimes been cited incorrectly in subsequent publications to infer that the nematode species naturally infests California pines, when in fact, Viglierchio reported only experimental studies conducted in a greenhouse. Early infestations found in nurseries and commercial productions would have been destroyed or significantly minimized through use of nematode-free planting stock and treatments of infected sites. Presently, the 1995 Santa Cruz nursery is no longer in business and non-existent.

It is important to note that with one exception occurring in 1995, over the past 30-40 years, D. destructor has not been detected through CDFA’s nematode surveys and nematode detection programs. From 2005 to 2009, CDFA conducted USDA CAPS sponsored statewide surveys for 22 target nematode species including D. destructor, associated with 24 major host plant species, including potato, tomato, iris and several other agricultural crops and ornamentals in California’s major cropping and nursery production regions. Ditylenchus destructor was not detected (Chitambar et al., 2008). Additional surveys, namely, potato cyst nematode surveys and golden nematode trace-forward surveys, and California’s citrus and golf course exotic nematode survey conducted by CDFA during 2006-2011, 2008, and 2012 respectively, and sponsored by USDA APHIS PPQ, failed to detect D. destructor in California’s potato seed and production fields, citrus, and golf course turf soils. Although, D. destructor was not the target species of those surveys, nematode extraction techniques deployed by the CDFA Nematology Lab would have enabled the possible detection of the potato rot nematode, if present. Furthermore, outside the afore-mentioned historical records, D. destructor has not been detected in CDFA’s regulatory detection programs involving plants grown in California soils. Those regulatory programs include phytosanitary certification or California-grown potatoes for export, nursery stock certification of California-grown strawberry, garlic, and fruit trees (CDFA Nematology Laboratory Pest and Damage Records). Also, the in-state presence of the nematode species has not been reported from other sources. Therefore, it can be inferred that the potato rot nematode, D. destructor, is no longer detectable in California’s agricultural production sites.

Hosts: The known host range of Ditylenchus destructor comprises more than 100 plant species from a wide variety of plants including ornamental plants, agricultural crops, and weeds. Solanum tuberosum (potato) is the principal host. Other economically important crops include Iris spp. (iris), Tulipa spp. (tulip), Dahlia spp. (dahlia), Gladiolus spp., (gladiolus), Rheum rhabarbarum (rhubarb), Trifolium spp. (clover), Daucus carota (carrot), and Beta vulgaris (sugarbeet). Weed hosts include, Cirsium arvense, Mentha arvensis, Argentina (Potentilla) anserina, Rumex acetosella, and Stachys palustris (EPPO, 2008).

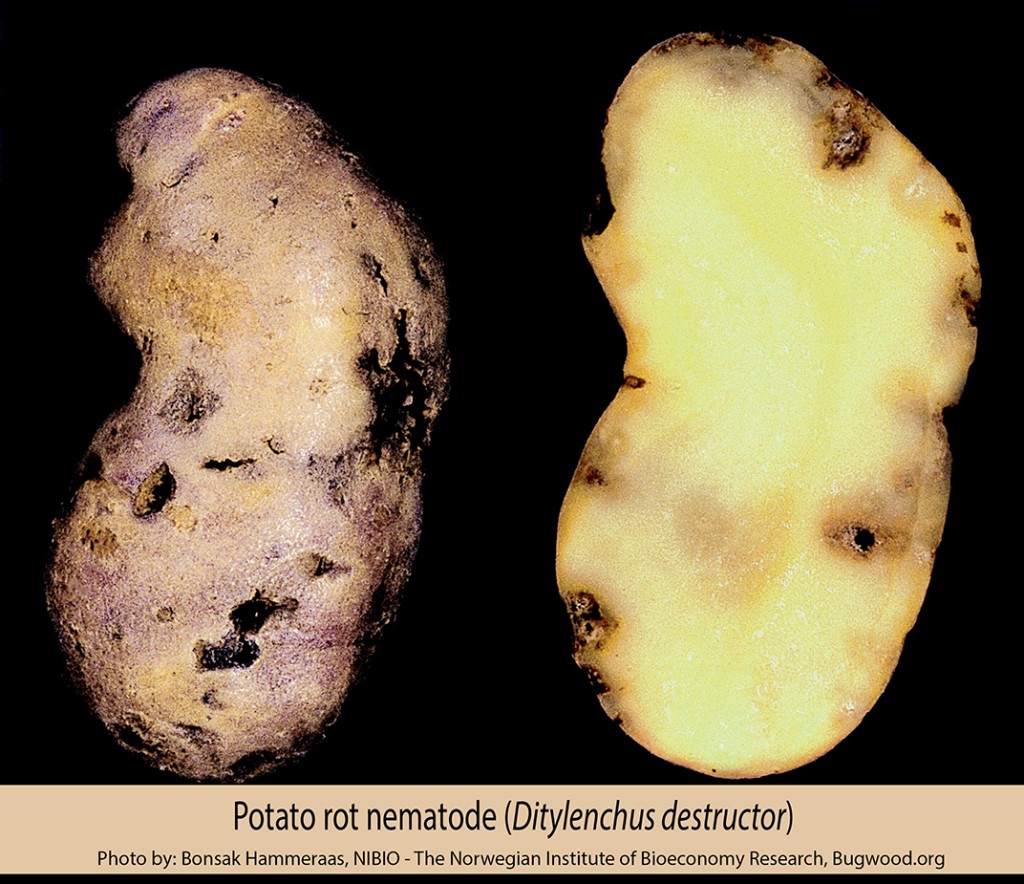

Symptoms: Generally, there are no obvious symptoms in above-ground parts of a plant infected with Ditylenchus destructor. Rarely when above ground parts are infected, symptoms may include dwarfing, thickening and branching of the stem and dwarfed, curled and discolored leaves (Sturhan & Brzeski, 1991). Heavily infested potato tubers may result in weak plants that eventually die. Common symptoms are discoloration and rotting of plant tissue. Symptom expression may vary with host.

Symptoms in potatoes: Initial symptoms appear in tubers as white spots under the skin. These spots later enlarge, become woolly in texture, and may have slightly hollow centers. Similar symptoms develop in dahlia tubers. Badly infected tubers have slightly sunken areas with cracked and papery skin detached from underlying tissue. The underlying tissue is discolored grey to dark brown or black bearing a mealy or spongy appearance. Discoloration is mainly due to secondary invasion of fungi, bacteria and free-living nematodes. In storage, rotting may increase with increasing temperature, without infestation spreading from diseased to healthy tubers (CABI, 2016).

Symptoms on flower bulbs and corms (e.g. tulips, iris): Infestations usually initiate at the base of a bulb and extend upwards to the fleshy scales producing yellow to dark brown lesions. Rotting may occur due to secondary invaders resulting in destruction of bulbs.

Symptoms on carrots: Transverse cracks are produced in the skin with white patches in the underlying sub-cortical tissue. Rotting may occur due to secondary invaders resulting in destruction of carrots.

Survival: Unlike the stem and bulb nematode, Ditylenchus dipsaci, the potato rot nematode does not have a resistant life stage (4th stage juvenile) that allows it to survive anhydrobiotically. However, D. destructor can survive on fungal hosts in the absence of plant hosts.

Transmission: The nematode can move only short distances on its own in soil, and is dependent on secondary means for its spread over long distances. The main means of transmission is with infested subterranean propagative plant parts (tubers, rhizomes, bulbs). Other means of spread include infested soil, irrigation water, weeds (CABI, 2016).

Damage Potential: Ditylenchus destructor causes rotting of tubers and other subterranean plant parts resulting in losses in crop growth and yield. Rotting may increase during storage.

Worldwide Distribution: Asia: Azerbaijan, China, Iran, Japan, Kazakhstan, Republic of Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Uzbekistan; Africa: South Africa; North America: Canada, Mexico, USA; South America: Ecuador, Peru; Europe: Albania, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Jersey, Latvia, Luxembourg, Moldova, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, Ukraine; Oceania: Australia, New Zealand (CABI, 2016; EPPO, 2008, 2016).

Due to unreliable detection records, Ditylenchus destructor is regarded as absent from the following countries and states: Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Australia, Haiti, Peru, Italy, Spain (mainland), British Columbia (Canada), Arkansas, Indiana, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Virginia. Its presence is not confirmed in West Virginia (USA) (CABI, 2016).

In the USA, Ditylenchus destructor has been reported from California, Hawaii, Idaho, Oregon, South Carolina, Washington and Wisconsin (CABI, 2016; EPPO, 2016).

Official Control: Ditylenchus destructor is on the ‘Harmful Organism’ lists for 45 countries: Algeria, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, European Union, French Polynesia, Guatemala, Holy See (Vatican City State), Honduras, Iceland, Indonesia, Israel, Jordan, Madagascar, Mexico, Monaco, Morocco, Namibia, New Caledonia, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, San Marino, Serbia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay, Vietnam (USDA PCIT, 2016).

On June 1, 2016, the USDA added Ditylenchus destructor to the ‘List of Pests No Longer Regulated at U.S. Ports of Entry’, however, the nematode pathogen remains actionable at certain ports of entry in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, or the U.S. territories (USDA, 2016).

Presently, Ditylenchus destructor is a “B’-rated, actionable nematode pathogen in California.

California Distribution: Presently, Ditylenchus destructor is not known to be present in California’s agricultural production sites (see “Status of detections in California”).

California Interceptions: From 1983 to 2016, Ditylenchus destructor has been detected in seven shipments of Iris spp. bulbs imported to Watsonville, California (CDFA Pest and Damage Records).

This risk potato rot nematode, Ditylenchus destructor would pose to California is evaluated below.

Consequences of Introduction:

1) Climate/Host Interaction: Evaluate if the pest would have suitable hosts and climate to establish in California. Score:

– Low (1) Not likely to establish in California; or likely to establish in very limited areas.

– Medium (2) may be able to establish in a larger but limited part of California.

– High (3) likely to establish a widespread distribution in California.

Risk is Medium (2): Ditylenchus destructor may be able to establish a large but limited distribution primarily within the States potato production acreage under cool and humid/moist climates. It is also likely to spread in cools regions where economically important hosts are grown and survive adverse climates in weed hosts.

2) Known Pest Host Range: Evaluate the host range of the pest. Score:

– Low (1) has a very limited host range.

– Medium (2) has a moderate host range.

– High (3) has a wide host range.

Risk is High (3): The main host is potato. However, the known host range of Ditylenchus destructor comprises more than 100 plant species from a wide variety of plants including ornamental plants, agricultural crops, and weeds. Other economically important crops include iris, tulip, dahlia, gladiolus, rhubarb, clover, carrot, and sugarbeet. Several weed hosts are also included.

3) Pest Dispersal Potential: Evaluate the natural and artificial dispersal potential of the pest. Score:

– Low (1) does not have high reproductive or dispersal potential.

– Medium (2) has either high reproductive or dispersal potential.

– High (3) has both high reproduction and dispersal potential.

Risk is High (3): Ditylenchus destructor has high reproduction potential. On its own, the nematode species can move only short distances in soil, and is dependent on secondary means for its spread over long distances. The main means of transmission is with infested subterranean propagative plant parts (tubers, rhizomes, bulbs). Other means of spread include infested soil, irrigation water, weeds. Therefore, it is given a high score for reproduction and dispersal potential.

4) Economic Impact: Evaluate the economic impact of the pest to California using the criteria below. Score:

A. The pest could lower crop yield.

B. The pest could lower crop value (includes increasing crop production costs).

C. The pest could trigger the loss of markets (includes quarantines).

D. The pest could negatively change normal cultural practices.

E. The pest can vector, or is vectored, by another pestiferous organism.

F. The organism is injurious or poisonous to agriculturally important animals.

G. The organism can interfere with the delivery or supply of water for agricultural uses.

– Low (1) causes 0 or 1 of these impacts.

– Medium (2) causes 2 of these impacts.

– High (3) causes 3 or more of these impacts.

Risk is High (3): Ditylenchus destructor causes rotting of tubers and other subterranean plant parts. Rotting may increase during storage. Therefore, the nematode species could lower crop yield, increase production costs, trigger the loss of markets, and interfere with transference of irrigation water that may aid in its spread from infested fields. Infestations of D. destructor could significantly impact nursery ornamental and cultivated mushroom productions.

5) Environmental Impact: Evaluate the environmental impact of the pest on California using the criteria below.

A. The pest could have a significant environmental impact such as lowering biodiversity, disrupting natural communities, or changing ecosystem processes.

B. The pest could directly affect threatened or endangered species.

C. The pest could impact threatened or endangered species by disrupting critical habitats.

D. The pest could trigger additional official or private treatment programs.

E. The pest significantly impacts cultural practices, home/urban gardening or ornamental plantings.

Score the pest for Environmental Impact. Score:

– Low (1) causes none of the above to occur.

– Medium (2) causes one of the above to occur.

– High (3) causes two or more of the above to occur.

Risk is Medium (2): Infestations of Ditylenchus destructor could significantly impact home/urban gardening and ornamental plantings, and trigger additional private treatment programs to mitigate potential crop loss.

Consequences of Introduction to California for Ditylenchus destructor:

Add up the total score and include it here. (Score)

-Low = 5-8 points

-Medium = 9-12 points

–High = 13-15 points

Total points obtained on evaluation of consequences of introduction to California = 13.

6) Post Entry Distribution and Survey Information: Evaluate the known distribution in California. Only official records identified by a taxonomic expert and supported by voucher specimens deposited in natural history collections should be considered. Pest incursions that have been eradicated, are under eradication, or have been delimited with no further detections should not be included. (Score)

–Not established (0) Pest never detected in California, or known only from incursions.

-Low (-1) Pest has a localized distribution in California, or is established in one suitable climate/host area (region).

-Medium (-2) Pest is widespread in California but not fully established in the endangered area, or pest established in two contiguous suitable climate/host areas.

-High (-3) Pest has fully established in the endangered area, or pest is reported in more than two contiguous or non-contiguous suitable climate/host areas.

Evaluation is ‘Not established’ (0): Presently, Ditylenchus destructor is not detectable or known to be present in California’s agricultural production sites (see “Status of detections in California”).

Final Score:

7) The final score is the consequences of introduction score minus the post entry distribution and survey information score: (Score)

Final Score: Score of Consequences of Introduction – Score of Post Entry Distribution and Survey Information = 13.

Uncertainty:

None.

Conclusion and Rating Justification:

Based on the evidence provided above the proposed rating for the potato rot nematode, Ditylenchus destructor, is A.

References:

Ayoub, S. M. 1970. The first occurrence in California of the potato rot nematode, Ditylenchus destructor, in potato tubers. California Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Plant Pathology, Sacramento, Special Publication. Number 70-2.

CABI. 2016. Ditylenchus destructor (potato tuber nematode) datasheet (full) report. Crop Protection Compendium. www.cabi.org/cpc/ .

Chitambar, J., K. Dong, S. Subbotin, and R. Luna. 2007. California Statewide Nematode Survey Project. California Plant Pest and Disease Report, 24: 59

EPPO. 2008. Ditylenchus destructor and Ditylenchus dipsaci. EPPO Bulletin 38: 363-373.

Sturhan, D. and M. W. Brzeski. 1991. Stem and bulb nematodes, Ditylenchus spp. In W.R. Nickle, ed. Manual of Agricultural Nematology, pp. 423–464. New York, Marcel Decker, Inc. 1064 pp.

Subbotin, S. A., A. M. Deimi, J. Zheng, and V. N. Chizov. 2011. Length variation and repetitive sequences of internal transcribed spacer of ribosomal RNA gene, diagnostics and relationships of populations of potato rot nematode, Ditylenchus destructor Thorne, 1945 (Tylenchida: Anguinidae). Nematology, 13: 773-785.

USDA. 2016. FRSMP: Pests no longer regulated at U. S. ports of entry. Last modified Aug 1, 2016. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/planthealth/plant-pest-and-disease-programs/frsmp/ct_non-reg-pests.

USDA PCIT. 2016. USDA Phytosanitary Certificate Issuance & Tracking System. https://pcit.aphis.usda.gov/PExD/faces/ReportHarmOrgs.jsp.

Viglierchio, D. R. 1978. Stylet-bearing nemas and growth of Ponderosa pine seedlings. Forest Science, 24: 222-227.

Responsible Party:

John J. Chitambar, Primary Plant Pathologist/Nematologist, California Department of Food and Agriculture, 3294 Meadowview Road, Sacramento, CA 95832. Phone: 916-262-1110, plant.health[@]cdfa.ca.gov.

Comment Period: CLOSED

Sep 27- Nov 11, 2016

Comment Format:

♦ Comments should refer to the appropriate California Pest Rating Proposal Form subsection(s) being commented on, as shown below.

Example Comment:

Consequences of Introduction: 1. Climate/Host Interaction: [Your comment that relates to “Climate/Host Interaction” here.]

♦ Posted comments will not be able to be viewed immediately.

♦ Comments may not be posted if they:

Contain inappropriate language which is not germane to the pest rating proposal;

Contains defamatory, false, inaccurate, abusive, obscene, pornographic, sexually oriented, threatening, racially offensive, discriminatory or illegal material;

Violates agency regulations prohibiting sexual harassment or other forms of discrimination;

Violates agency regulations prohibiting workplace violence, including threats.

♦ Comments may be edited prior to posting to ensure they are entirely germane.

♦ Posted comments shall be those which have been approved in content and posted to the website to be viewed, not just submitted.

Pest Rating: A

Posted by ls